To Veil or Not to Veil

By Ayaan Rajan and Paul Issaurat

In September 1989, three Muslim students, of North African origin, attended school in Creil, France, attired in veils that covered their hair. Upon entering the school premises, staff members demanded the girls remove their head coverings. However, they did not comply, for which they were subsequently expelled. This conflict, known as the Headscarf Affair, was the tip of the iceberg in a decade that witnessed over 100 Muslim girls being banned from attending school due to their head-coverings.

Through the 21st century, the French government has continued with its efforts to drive the veil out of the public sphere, most notably schooling institutions. The long-standing conflict between the French government and Muslim women has surfaced in international media spotlight over recent years. Muslim women have received worldwide support in their endeavors towards assimilation in French society. However, the majority of French nationals have remained united in their opposition to Muslim veils in schools, a perspective rooted in the ideology of French secularism.

Why is France restricting the wearing of the veil for Muslim women? What are the views of Islamist states versus secular states on this controversy? Is the “ban” on the veil related to growing Islamophobia in France or are there other factors to consider?

Veiling in Islam

The process of veiling in Islam is said to date back to the era of Prophet Mohammad, whose first wife, Khadija, is regarded as the first female practitioner of Islam. She adopted the hijab, one of the many forms of veiling for Muslim women which can be observed in the image above.

Head-coverings have since retained their significance for the female Islamic community, however, questions have been raised on whether it is an obligation or enforcement for women to wear them.

Western societies argue the veil is a symbol of inferiority for women in Islam and is a portrayal of the oppression they have supposably been subjugated to. However, Muslim women have articulated their wearing of the headscarf is a demonstration of their piety and adherence to Allah.

Muslim Women in France

Today, Muslims represent 8.8% of the French population, with Islam being the second most practiced religion in the nation. The Muslim community began to grow in France through the mid-late ’90s as a result of the influx of immigrants from French colonies in Africa.

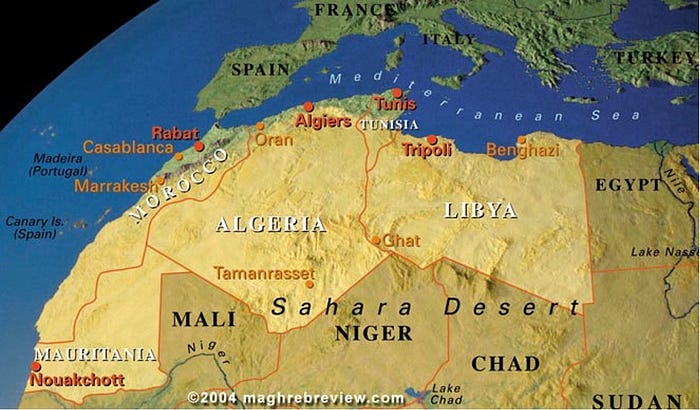

Maghreb’s, residents of the Western-most part of North Africa, represented the majority of the immigrant community and largely practiced Islam. Maghreb is the umbrella term for residents of Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, and Libya. Maghreb women often attired in veils in the French public sphere, perpetuating their continued disputes with school staff, government agencies, and society at large through the ‘90s.

In December of 2003, President Jacques Chirac espoused the entrenchment of a law that would exclude symbols of religious expression in public schools. This was not limited to the veil alone, and also included all ostentatious symbols of religion including the Jewish Kippa and large Christian Crosses. In 2010, the government banned full-face covering, including the Burka and Niqab, in public spaces such as streets, parks, and transit systems.

Current French President, Emmanuel Macron, has expressed his concerns over what he indicates as “Islamist Separatism”. Earlier this year, The Senate passed the Anti-Separatism Bill, which Macron suggested would neutralize the threat of Islamic extremism in France. The Bill articulates strict patrolling of places of worship, restrictions on home-schooling of Muslims, and banning civil servants from wearing religious symbols such as the head-covering for Muslims. While the French government has advocated that the bill is not intended for Muslims, religious women suggest it imposes restrictions on their livelihood and freedoms.

This conflict has resulted in the sharp divide between French politicians and Muslim Migrants in France today, as France has persisted with efforts to drive the veil out of the public domain. Islamists within France have protested against the government, citing it as discriminatory and Islamophobic, and they have received support from Western and Islamist states worldwide. However, more than 60% of French nationals have suggested they support the implementation of a law forbidding the veil in schooling institutions.

The Islamist Perspective

Attempts from the French Republic to prohibit the wearing of the Islamic veil in the public sphere have been accompanied by outrage from the Muslim community and abroad. Many Muslims within France have articulated feelings of inferiority, segregation, and mitigation of fundamental freedoms perpetrated by the government.

Caitlin Killian, Assistant Professor in Sociology at Drew University, conveys 41 interviews she conducted with female Maghreb’s, in her ethnography, The Other Side of the Veil. About two-thirds of the interviewees conveyed that they should be permitted to attire in veils in public spaces. Half of these women, who were elder and did not have an academic background, articulated that the veil is not considered a symbol, hence it should not be forbidden in schooling institutions. They argued that veiling is a habit, and as long as the Muslim girls remain respectful and work hard while at school, they should not be restricted from wearing it.

The other half of the Muslim women who suggested veiling should be allowed on school premises were younger, and most of them had pursued post-secondary education. These women suggested they can understand France’s reasoning for prohibiting veiling in schools, but suggested children of immigrants should be allowed to represent their religious and cultural beliefs. Many even suggested they oppose the veil themselves but they propound that all individuals should be entitled to self-liberty and the state should not dictate the actions of Muslim immigrants.

Muslim women within France have continued with their protests against the French government, and have been successful in spotlighting the issue in global media outlets. #HandsoffmyHijab and #FranceHijabBan were trending worldwide earlier this year on social media. Amnesty International has urged French lawmakers to renounce the bill which prohibits veiling in the public domain, as they argue it will lead to further discrimination, and division, within France.

The French Perspective

It could be said French restrictions concerning the wearing of the veil, burqa, or other religious accessories have two origins: the French principle of “Laïcité” and growing opposition to a perceived Islamist threat. The restrictions around the wearing of the veil, or any visible religious symbol in school or for public workers while exercising their professional duties originate from the long-standing principle of “Laïcité”, while more recent restrictions on the burqa, for example, may stem from growing domestic opposition to Islamism.

To better understand secularism in French public institutions, an interview was conducted with Daniel Le Gal, a school inspector of the national education program. He explained the official justifications of the restrictions as a school inspector and gave us his thoughts on more recent restrictions in France.

Since the 1905 law separating the State from the Catholic Church, the French state has portrayed itself as neutral concerning religious matters and instituted a republic that neither recognizes nor supports any religion. Our interviewee stated that the 1905 law is a “law of freedom that allows one to express themselves”, and further explained that religious signs are allowed in public, citing only two contexts of restriction: in school and while exercising professional duties as a civil servant.

“Laïcité”, a principle aiming to protect?

Daniel tells us that children are not allowed to wear visible religious signs in public school as “it is considered that at that age, they are not able to have a free will”, that the ban “aims to protect girls [and boys] from a third-party influence”. He illustrates the concept by pointing out that women are allowed to wear the veil in university “because we consider that adults […] could choose the fact of wearing or not this religious sign”. He further developed that as a school inspector, he also inspected schools where children are allowed to wear religious signs; “These private schools exist, but they will not be subsidized by the state”, marking the historic separation the state wishes to keep from religious institutions.

“I am a representative of the state, and the state is neutral”.

While working for the state, thus representing it, a French civil servant must abstain from manifesting religious opinions, which includes wearing religious signs. The reasoning behind the restrictions concerns the ideological representation of the state. “It protects the other users,” says Daniel, “I, as a Catholic or Muslim, do not have to impose my religion [or political partisanship] on you […] the idea is to express the neutrality of the state”. This has been in place since 1905, and while the state has kept its secular position, it has also passed and ratified numerous laws and conventions guaranteeing freedom of religious belief and practice, in public or private spaces.

French “integration”, an ongoing debate

SciencePo professor Mirna Safi affirms integration in France implies the convergence of immigrant characteristics to average French characteristics. While this is still an ongoing debate in France, it’s clear France asks its population to respect its republican values, founded on values like “Laïcité” that exclude religion at times. The incompatibility between those values and values that prioritize religious membership over collective identity creates some of the tensions that we can observe today. One is allowed to practice their faith freely, but if the practice includes a voluntary, or involuntary exclusion from society, it is not accepted in France. The burqa or niqab cover women in a way that implies an exclusion from society, which pushes women into a situation of “inferiority, incompatible with the [French republic’s] principles of liberty, equality and human dignity”, at least according to the French government (Légifrance, 2011).

While the ban of full-face coverings marks the denunciation of the burqa by the French government during the rise of Islamic fundamentalism, the Anti-Separatism bill passed in 2021 is represented as a more thought-out reaction to Islamist terrorist attacks that have taken place on French territory in the past decade. The Bill may pose ramifications for all people who practice their faith in France, but its official aim is to seriously constrain radicalism, rooted in domestic underground associations or abroad. It increases the financial accountability and transparency of religious associations and home-schooling and reinforces the application of republican principles for civil servants and associations receiving government subventions. It also includes “vaguely defined concepts” that would leave space for discrimination according to Amnesty International, thus its application must be observed in detail to perceive its actual discriminatory impact on law-abiding citizens and its efficiency in preventing radicalism and terrorism.

Although the application of secularism in school and for civil servants is widely accepted and is believed to unite the nation (Viavoice, 2020), it must be differentiated from policies that emerge from a fear of Islamism that generates more debate, like the ban of the burqa for example, as they could be aimed at specific minorities, unlike secularist policies.

Conclusion

Muslims within France have argued that they are subjugated to discrimination by the French government, a view largely supported by Western and Islamist States abroad. However French nationals have conveyed that France’s history is grounded in secularism and convergence to common values. The government propounds that symbols of religious expression are accepted but they seek to mitigate its influence in governance and the construction of the French identity.

The two sides remain very divided in their opinions on the issue and have been incapable of finding a tangible solution that will best suit all associated parties. So how will this issue transpire moving forward and how will the stranded relationship between the French government and the Muslim Community be addressed?

While french radical-right-wing leaders grow in popularity and foreign criticism accumulates, one could fear that french policies evolve in a way that excludes specific minorities. As risks are high, some could argue that constitutionally “the Republic is united and indivisible” and that safeguards against discrimination, such as the principle of “Laïcité”, must not be eroded, but rather adapted and explained so that it respects common values.